A French postal worker, who used to fly the coast of Africa delivering postal dispatches, wrote a delightfully witty book I read long ago. In the story of Le Petit Prince, the author, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, talks about how his plane broke down in the desert one time. He narrates the tale as his pilot self, recounting the story of a small person who approached him while trying to repair the plane. This character claimed to be an alien who had been hopping planets prior to landing on Earth, which had such tremendous gravity that it couldn't be escaped. Being stuck on Earth didn't seem to be a particular bother other than the fact that it meant he could never return to his origin planet, where his favorite flower lived. The story turns into a narrative on the nature of love and loss as the alien prince tries to adapt to the ways of Earth and comments on all the strange characters he'd met on the various planets prior to getting marooned in the desert with the pilot.

I recount this tale because I've been thinking about cartography a good deal recently. The efforts of various companies to create proprietary maps remind me of the "businessman" character in Antoine's story. (See chapter 13.) He was too busy to talk to our protagonist because he was tabulating all the stars. He asserted that by keeping record of the stars he was owning them. The prince channels the perspective of Chief Seattle that it is preposterous to assert that one can own nature. (In Chief Seattle's case it was native tribal land he was being ask to sell to the US government.) The augmented reality mapping community isn't trying to own spaces, but rather create a utilitarian linking model, metaphorically similar to the Global Positioning System (GPS) but specifically for the shared context between people for use in location-based content discovery and information sharing.

You might think we could just have one app to rule them all, and that all location-based content should be visible within that. But this limits utility. It calls to mind the parable of Śāntideva, the Tibetan monk who mused:

“Where would I find enough leather

To cover the entire surface of the earth?

But with leather soles beneath my feet,

It’s as if the whole world has been covered.” *

Getting everyone on Earth to use one tool in order to benefit from location-based data isn't feasible nor optimal, any more than covering the earth with leather. It would spur a new digital divide problem on top of the one we already have, and become too cumbersome to maintain and update securely. The internet is a more scalable approach than an app-siloed approach too. The web's pooled effort of millions of developers, curators and contributing users are already adept at working on rich content generation, with adaptable sharing, access and security already taken care of. So in the location-based web, we have to think about renderings of web content in a way that can be shared by thousands of browsers, apps and location-"aware" tools that don't have screens. This will allow individuals worldwide to put soles beneath their feet to navigate this information terrain in diverse and dynamic ways.

To build this shared-content layer, we need engineers, artists, business teams and shared standards for engagement and architecture across millions of personal navigation devices. Rather than the celestial businessman who seeks to chart the stars alone, we need creators with the philosophy of an open-source cartographer. When the world-wide-web of hypertext documents charted the course for our internet of today, it started with a small interlinked corpus of nodes, which then expanded exponentially in the 1990s as millions of contributors posted and linked their own creations with others. I remember early approaches for content sharing and navigation depended on web-rings where site hosts would link their content to other sites of known related content. Bloggers created their own specialized hubs of niche content. Companies like Yahoo, Excite and LookSmart hired hundreds of content curators to pull in sources of new content as the web grew. Netscape’s Open Directory Project and Wikimedia achieved similar content mapping databases for multiple languages around the world even without a corporate sponsored business model. Then once, the scale of web content grew faster than could be aggregated or charted efficiently a purely algorithmic model was needed to scale the corpus of the web efficiently, leading to the web crawlers and Boolean web query models we have for sifting content today.

Web search engines of today didn’t yield their value from a top-down approach, but rather a bottom up. They gained their utility for us by mimicking the way that web developers inter-link and label their content for discovery. Early algorithmic search engines (Altavista, Hotbot, Inktomi, Fast, Bing, Google for instance) would crawl the web much like a spider, following the way each thread of the web linked to every other and ascribing weighted value to different kinds of connections site hosts would paste into their html by way of “anchor-text links.” It was crowd-sourced in a way that made it more dynamic and resilient than any single company or group could create.

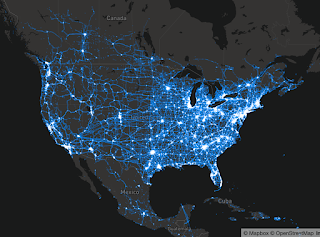

The spatial web will be woven similarly, in a crowd-sourced way with location reviews of restaurant goers, measured velocity of sharing actions and graffiti-style content postings that happen in the physical world. The search engines of this cartographic space will prove their value by filtering millions of tread paths of those wandering its trails and leaving notations for others, reinforcing the well-trod paths as potentially of utility to others just like the keyword searching model we’ve become accustomed to, which replaced the editorially curated/recommended web indexes of the past.

While the location-based internet has had many exciting phases of evolution over the past decades, it is rising to a fever pitch these days as a broad array of well-funded companies are starting to plan new utilities to map digital services over our shared physical space. The current pace of technology advancement here is a fascinating rabbit hole of strategies for cartography enthusiasts like me.

I became particularly interested in cartography during my international travels (50 countries to date) when I would use tools derived from the Open Street Map's open source database of physical locations to plan, journal and photographically document my journeys. Sometimes I was able to find my way about with digital maps in a way that was not possible with market-available paper maps that I'd bought. (In many cases, the places I'd go were not mapped precisely by Nokia Here, Bing nor Google Maps in a useful way. For dense cities, those services are great. But for the digitally disconnected regions of the world, they don't provide the anticipated utility.)

I care about expanding this portion of our technology because I believe there is tremendous good that we can do for our community, and those who come after us, by facilitating greater levels of information layering on our physical world and the chronicling of information that can be available to people anywhere specific at a moment's search. There are tremendous resources that we've created in the corpus of the web that are not directly accessible in a given location without particular forward-leaning effort with keyword querying of web content. That's something we can address with good tools and intuitive user experience models that make the web generally more applicable to the daily lives of people in specific places.

Now that Virtual Reality gaming has advanced to a relatively mature market, several companies are now pushing the 3D models of gaming engines (such as Unity and Unreal) to create simulated virtual overlays of the shared space we live in. You may be concerned about these advancements from a safety perspective, with good cause. Distractions can be a danger in any context. The hazards of digital overlays in the real world are already being tested by pioneering companies who will be mindful of this. With Niantic's gaming layer (discovered through mobile phone screens, and eventually digital glasses) there can be risks of people being distracted from real-world safety issues. Niantic themselves have taken care to ensure that users don't engage with their games in ways that would put them in physical danger. With the release of more eyeglass products from Snapchat, Nreal and Facebook Aria, we'll start to see more social utility, services and commerce advance this trend beyond the well-established use of Augmented Reality in the workplace, which has been the focus of earlier efforts of Microsoft, Google and Magic Leap. Just as the mobile phone and automobile industry have taken measures to reduce distracted driving, caused by the proliferation of mobile phone usage in the wrong contexts, we can anticipate the industry addressing our concerns about such distractions outside of the driving context as well as these "mobile glasses browsers" become common in public.

Before departing the Google Maps division, the Niantic project had an interesting angle for this. During the development of their first game, Ingress, I met the team at the San Francisco Game Developers' Conference. They explained

that there was a commercial value to moving people around in places. If

they were to place an Ingress portal in a location that happened to be a

store, those people playing Ingress nearby might eventually walk into

that store to buy something. So location-based incentives may be the economic value to

a cartographic platform that could influence where people decide to go in a specific location. This is also of great value for travelers, who are actively looking for tips on how to discover a location and which places to visit, book lodging with, or discover culinary and cultural opportunities.

Around the same time as that conference, I'd learned of a company that was creating a real-world Pac Man game that would drop little digital treats on their driving game to encourage people to create a digital layer of mapping that they could claim to be their proprietary travel-based index of the world. At a TEDx talk in Silicon Valley their product manager described the perils map routing. She suggested that the Waze app could leverage the willingness to explore of their users, somewhat like a group of foraging ants, to "random-walk" the Earth until they knew the real-time travel velocity of every navigable path on the planet. It struck me that this was a slight ecological nightmare if it was gamifying the concept of driving the roundabout way, just for a digital treat, instead of navigating in a straight path, which would require the least expenditure of resources, even if not time. Perhaps over time the initial waste of the indirect-route incentive would lead to traffic reduction for subsequent users who might not have known about an alternative efficient route that was better than the route that a larger map service would recommend. Ultimately, Google decided that the gamified approach of Waze and the active "contributor" community of people reporting road hazards and route feedback was enough incremental value over Google Maps alone to merit an acquisition of the company, while the decided to spin off the Niantic project as a stand-alone company.

If you happen to be a VR enthusiast, you probably have seen the rich 3D environments that Google Earth have rendered specifically for VR-ready devices. You can fly though the streets of New York, Chicago or San Francisco seeing a spatially accurate depiction of these major cities. You may then be surprised to see that a similar level of effort has not been put into cultural or historically significant world locations. The reasons may seem obvious. The city-scapes are assembled using Google's lidar photography (Such as the cameras on Waymo cars) combined with known information about the buildings that make up the city's topographical 3D structure. Obviously you can't drive a Waymo car through Chichén Itzá. An altogether different approach needs to be applied. One of Google's contributors explained that for areas that are not navigable by car to map with lidar, you must use aerial photography with photogrammetry (stitching of photos from different angles) to create depth maps. Putting San Francisco on the map is therefore, very easy. Putting Chichén Itzá, Petra or Angkor Wat on the map is stunningly hard. It's a finite expense, but the benefit from doing it doesn't yet outweigh the cost of doing it. It's just a matter of time and logistics though.

Considering the economic problem that leaves so much of Google Earth unmapped in 3D relief, you might wonder how AR is going to be any different. This is an issue that a bunch of people are trying to solve actively right now. The good news is we can use the hive-like behaviors of humans to accomplish it, just like the Waze team did for the streets of the US. But there needs to be some benefit or value of participating that incentivizes people to do the contribution work necessary to make a good map. That's where people like me come in. As a mapping contributor, uploading photos, making reviews and leaving tips for travelers, I'm doing the necessary work to create the content rich location layer across that will eventually populate our smart-glasses, automobile dashboard screens and social traveling apps.

If it all the work had to be done by advertising companies, then every location you go to you'd be hearing navigation tips like "Turn left at the Wendy's then go straight to the 7-Eleven, where you bear a right, you're at your destination when you can see a Home Depot on the opposite side of the street." All that overt advertising would probably drive attrition of the navigation tools because the heavily-sponsored environment is annoying and distracting over time. It reminds me of the skyscraper in Hong Kong that for years had the giant text "AD HERE" on its Kowloon-facing side. The incentives need to be subtle, like the "Pokémon Go Incense" and "Poké-lures" that Niantic provides for individuals to draw customers to the proximity of commercial businesses when they need foot traffic. It's more appropriate to leverage context without being so overt as to say, "To get your next Poké Monster, walk into the store next to you and buy a soda, scanning the QR code on its side." You may in fact do those things of your own volition. But being instructed to to them in order to unlock a level of a game is annoying.While these incentive schemes work well for large companies with a broad user base, smaller developers and content creators will have a challenge trying to create real-world content publishing. For instance, if I had a large photogrammetry map of Chichén Itzá, how could I get that content to someone who could benefit from it? Generally, I'd have to have a content marketing strategy to try to find the person who needs it when they need it. I'd have to place marketing materials at the locations where the need for that 3D map might arise, in the real world, or do marketing campaigns in search engines or travel portals to let people discover it. So not only do I have to pay all the money necessary to accomplish the 3D map generation, I have to ensure people can find it. That's a particularly baroque undertaking. There are indeed people who are working on the first part of the problem, making the 3D models with lidar and photogrammetry stitching for the benefit of posterity. Yet people with those talents don't typically have the marketing savvy to address the discovery side of the user experience. That's where the free-to-index search architecture that popularized sites like Yahoo!, Bing and Google come in. But the mechanisms that made those companies possible can't be directly extended to solve this search challenge. A new means of sifting data needs to be deployed for this case.

In the US, QR-codes are typically used to engage location or topic-specific content queries from a physical sticker or billboard. The team at Verses Labs proposes a global domain registry approach for location mapping that is similar to the DNS lookup table approach of the Internet domain registry legacy model. (The administrative body for DNS registrations is called ICANN.) Recently, an Estonian company, Over Holding, has proposed a concept whereby developers share a blockchain record of location assets with a tenancy privilege for developers who publish to or buy the location "hexagon" where the AR content will be placed. This isn't meant as NFT land grab hype. They envision a model whereby virtual estate needs to be able to fluctuate up and down in price in a means similar to the open competitive market that defines price of physical real estate that it is emulating. What Clear Channel (US) and Ströer (EU) is to the physical advertising world in billboard marketing, they'll mimic with digital equivalent of "rights to display" in the shared space that developers leverage on their digital monetization architecture.

While the ICANN domain registry approach yielded many free market search engines in the past, this could be an exceedingly complex centralization effort to run for the entire globe. Whichever approach for location-based posting/indexing emerges, it will need to develop defenses just like the web-index techniques for spam prevention, content preferences, filtering and ephemerality/freshness if it is to become valuable and beneficial to us on a broad scale.

It will be interesting over the next few years to see how the discoverability and publishing rights for location advance. It's too early to tell whether we'll stay in-app for the next decade or go toward one of these more decentralized models for content sharing. A few more companies need to jump into the pool before a good standardization effort for cross-platform content visibility and share-ability emerges. While it may seem a Sisyphean effort to chronicle and map the world when we don't know yet what the eventual shared standard is going to be, I think it's a valuable expense of resources for the web of tomorrow, which should ideally be specifically relevant to us based on where we are, not just who we are.